A Patchwork Ceiling

I’ve never been good at buying used, which is a problem because I do it almost exclusively. I get nervous inspecting the item in front of the seller, as if I’m the one trying to impress them. Back in college, I spent a summer living with my brother in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. His apartment lacked AC, and his other roommate had converted the living room into an impromptu halfway house for unvaccinated street cats with too many toes, so we spent the majority of our time hopping from one park to the next. If I wanted to keep up, I thought, I’d need a bike.

So I found a cool vintage frame on Craigslist, silver with drop handlebars, and agreed to the meet the seller at the McDonald's on the corner of Parkside and Ocean Avenue. I’m sure I made a sharp and sophisticated joke about Yellowcard, a great band that we all remember. It must have been a weekend; the intersection was flooded with traffic and people on foot, and I remember walking past the man several times before noticing the bike parked beside him. This is where I always fail. The minute I see the used item and the seller standing next to it, anticipating the quick exchange of money, I freak. My palms get sweaty. My heart rate spikes. I feel like I’m committing some tacit transgression, something I should be ashamed of. I rarely look them in the eye. I laugh when they say things that aren’t even close to jokes. I crumble.

He told me the bike was $200. We had agreed on $150. It was clearly too small. The brakes sounded like my food processor. Rust snowed down from the chain when I rotated the pedals. It was a terrible bike. It was the worst bike.

“It’s perfect,” I told him. “Thanks so much for meeting me here. It’s exactly what I needed.”

So I’m not great at buying used. Last October, when I met Craigslist Ray in Stuart, Iowa, all those same feelings came rushing back. Online, Ray had told us all of the plumbing was in great shape. Later, we found out all of the water lines had cracked. Online, Ray had told us all of the electrics were in working order. Later, we found out the main overhead lighting system was down and the taillights were broken. As you know from previous posts, what I drove home with was not exactly what I came for.

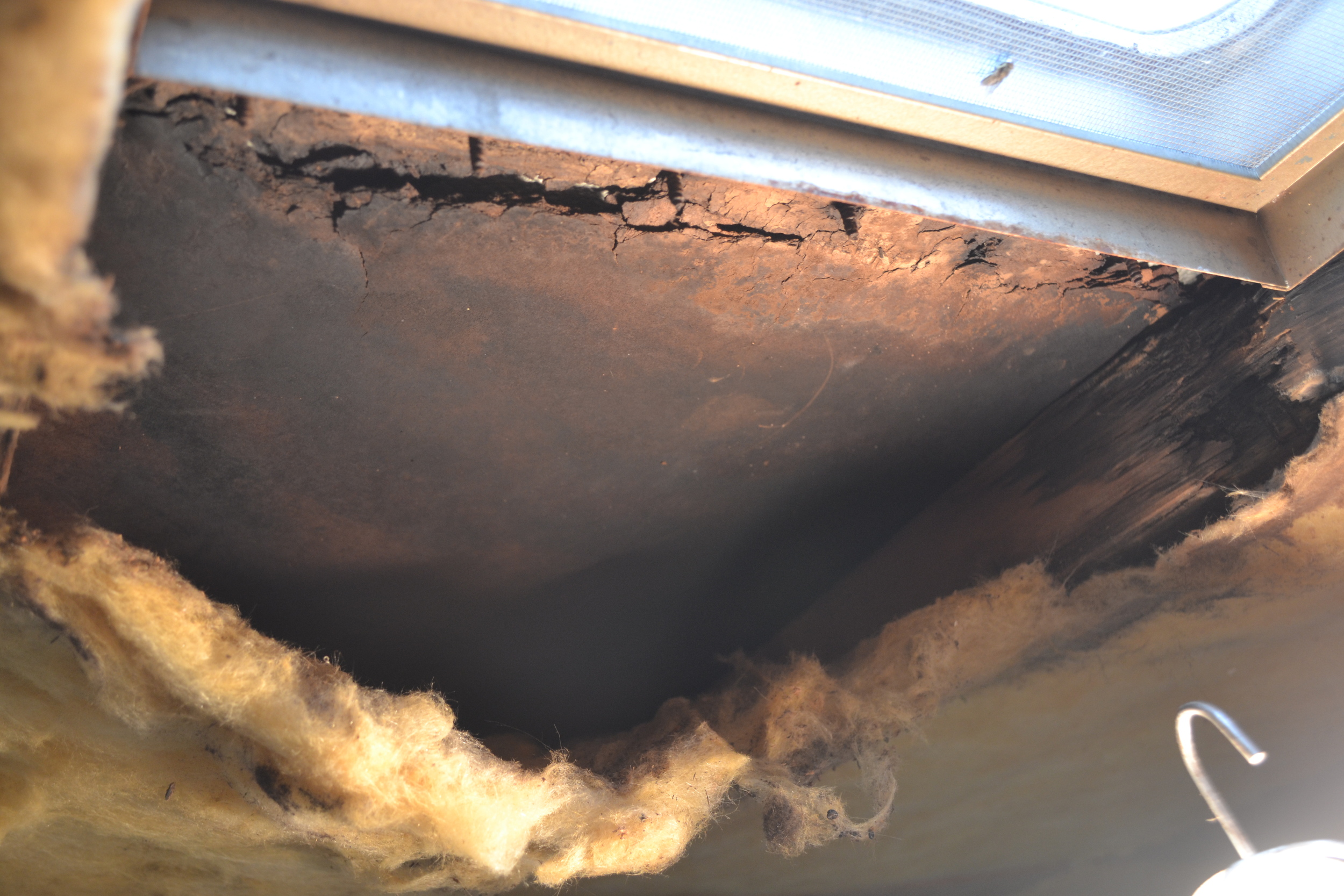

The one area of disrepair that Ray had been upfront about was a small hole in the corner of the ceiling. He showed the hole to me again in person. He said it probably wouldn’t take much work to fix it. I laughed so quickly I cut him off, then said something stupid like, “Heck! No big deal! Everything else looks like it’s in perfect shape!” What I had meant to say – what I was thinking – was that I had no idea if that hole in the corner was of serious concern, and that either way, I did not have the skills to fix it.

But Jerry (dad/foreman/optometrist/former Scoutmaster) did. During one of our first weekends back in Broken Bow, we tackled that hole head on. After poking around a bit with various tools, it was clear the whole area had rotted due to water damage. Tearing back the ceiling paper confirmed as much. To fix it, we cut out the rotted area between two joists using a reciprocating saw. Upon closer inspection, part of the joist was nearly rotted through as well, so we cut that out and reinforced it with a fresh 2x4. Then, to fill the square gap in the ceiling we just had removed, we cut a piece of 3/16th inch plywood exactly that size, and used the pneumatic nailer – in addition to a good thread of construction glue – to fix it back in place. To see that fresh plywood pressed tight against the ceiling, completely sealed with glue on all sides, was a catharsis I would come to feel time and again in completing Elsie’s renovation.

Of course, very few of Elsie’s repairs were so simple as to warrant only a single paragraph. In the weeks to come, as we stripped away the old contact paper on the ceiling in order to replace it with new material (more on that in a separate post), we found further water damage, more rotting, another hole, and then another and another. As you might expect, most of the water damage occurred around ceiling vents or joints in the frame, anywhere that might allow rain or melting snow to pool up. We tackled each one in the same way until, finally, we had worked our way back from the far back corner to the front door. At least half of the ceiling had been patched and replaced, a checkerboard of the old and the new, but more importantly all of it was now structurally sound. And in the process, we answered the question of what lies beneath. Answer: rotted ceiling joists and yellow insulation littered with the carcasses of bugs long dead.

In total, the process took a few days to complete, though the work was on-again, off-again. We'd patch a hole, congratulate ourselves on a job well done, and then each of us would spot a different area that likely needed the same treatment. We'd sit on that belief for an hour, a day, afraid to acknowledge the extra work ahead. Finally, one of us would confront what we had found. Then Jerry would shake his head, measure the area and wander back to the shed to cut more plywood. He and I would lift the panel to the ceiling, take turns nailing and gluing and sometimes screwing it into place, and wait until someone pointed out the next issue. Without fail, there has always been a next issue.